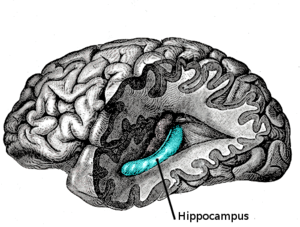

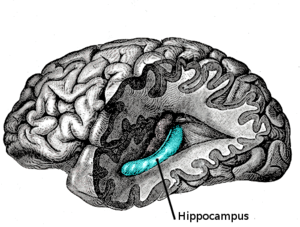

Image via WikipediaSome of you will be finding your thoughts turning to revision. In getting ready to write essays in exam conditions, you might find it useful to look back at this earlier post on the topic. Otherwise, you could do no better than to have a look at an excellent blog post by Jon Simons, a researcher into the cognitive neuroscience of memory. Jon's post tells you how to use scientific findings from memory research to hone your revision skills. You can check it out here.

Image via WikipediaSome of you will be finding your thoughts turning to revision. In getting ready to write essays in exam conditions, you might find it useful to look back at this earlier post on the topic. Otherwise, you could do no better than to have a look at an excellent blog post by Jon Simons, a researcher into the cognitive neuroscience of memory. Jon's post tells you how to use scientific findings from memory research to hone your revision skills. You can check it out here. Monday, March 21, 2011

Revision: Keep it scientific!

Image via WikipediaSome of you will be finding your thoughts turning to revision. In getting ready to write essays in exam conditions, you might find it useful to look back at this earlier post on the topic. Otherwise, you could do no better than to have a look at an excellent blog post by Jon Simons, a researcher into the cognitive neuroscience of memory. Jon's post tells you how to use scientific findings from memory research to hone your revision skills. You can check it out here.

Image via WikipediaSome of you will be finding your thoughts turning to revision. In getting ready to write essays in exam conditions, you might find it useful to look back at this earlier post on the topic. Otherwise, you could do no better than to have a look at an excellent blog post by Jon Simons, a researcher into the cognitive neuroscience of memory. Jon's post tells you how to use scientific findings from memory research to hone your revision skills. You can check it out here. Wednesday, December 8, 2010

Getting your references right

The people marking your essay will be expecting you to use a standard referencing style. For Durham psychology students, this means APA style. APA style is described in detail in the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, now in its 6th edition. Note that earlier editions define the referencing style in slightly different ways, so you need to keep up to date by following the new edition.

You will find copies of the 6th edition in the library. A very useful brief guide to the referencing style is provided by the Library of the University of Waikato, New Zealand. You can also find information on APA style here.

Getting referencing style right means two things. Firstly, you have to get your in-text citation style right. This refers to the way you reference an article or book in the body of your essay, e.g. Jones (1990). Secondly, you have to make sure your reference list at the end of the essay is up to scratch. Here, you need to pay attention to issues such as: punctuation, indents and paragraph style, citing secondary sources, citing edited books and chapters in edited books, citing information gleaned from the web, etc. The rules may seem complex and long-winded, but they are extremely important. APA is a very widely used style and it's worth getting it right from the start.

You also need to check that everything you cite in the body of the essay appears in the reference list, and vice versa. Markers will be very sensitive to style errors (some psychologists even say that they think in APA style) so you need to check this aspect of your essay very carefully.

Remember that your word count usually excludes the reference list at the end, but of course you need to check your handbooks and other instructions to establish what applies for each particular piece of work.

As an exercise, see if you can spot the errors in the following paragraph (with thanks to Elizabeth Meins). I'll post answers in a later post.

You will find copies of the 6th edition in the library. A very useful brief guide to the referencing style is provided by the Library of the University of Waikato, New Zealand. You can also find information on APA style here.

Getting referencing style right means two things. Firstly, you have to get your in-text citation style right. This refers to the way you reference an article or book in the body of your essay, e.g. Jones (1990). Secondly, you have to make sure your reference list at the end of the essay is up to scratch. Here, you need to pay attention to issues such as: punctuation, indents and paragraph style, citing secondary sources, citing edited books and chapters in edited books, citing information gleaned from the web, etc. The rules may seem complex and long-winded, but they are extremely important. APA is a very widely used style and it's worth getting it right from the start.

You also need to check that everything you cite in the body of the essay appears in the reference list, and vice versa. Markers will be very sensitive to style errors (some psychologists even say that they think in APA style) so you need to check this aspect of your essay very carefully.

Remember that your word count usually excludes the reference list at the end, but of course you need to check your handbooks and other instructions to establish what applies for each particular piece of work.

As an exercise, see if you can spot the errors in the following paragraph (with thanks to Elizabeth Meins). I'll post answers in a later post.

Considerable evidence has now accrued to support Bowlby’s 1969, 1973, 1980 contention that attachment security is transmitted from one generation to the next. The link between autonomous parental attachment representations as assessed using the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI: George, Kaplan and Main, 1985) and a secure infant–parent attachment relationship has been found in various countries and in wide-ranging populations, (e.g. Aviezer et al., 1999, Dozier, Stovall, Albus and Bates, 2001, Fonagy, Steele & Steele, 1991, Main, Kaplan & Cassidy, 1985; Pederson, Gleason, Moran, & Bento, 1998; Steele, Steele, & Fonagy 1996; Ward & Carlson, 1995).

Related articles

- How to Write an APA Paper (psychology.about.com)

- A Guide to APA Format (psychology.about.com)

Monday, May 3, 2010

Writing essays under fire

It's that time of year, and you will all be thinking about how best to deploy your essay-writing skills in the heat of the exams. Much depends on your revision preparation, of course, and on how you manage to pull it all together on the day. Of course, everything that has been discussed on this blog is potentially relevant to putting together a good essay in the exam room. But I think there are also some useful things you can do specifically in getting ready to write a lot of words in a short time.

To show what I mean, I'm going to suggest that you go back to some of those earlier issues about structuring an essay. Remember that I suggested that you start by looking at your word limit and then work out a possible structure in terms of paragraphs. The same strategy can work in an exam.

In an exam, of course, you don't have a specific word limit. But you do have a time limit, so start with that. Let's imagine that you have a two-hour exam in which you are going to have to answer two questions: one hour per question.

Planning is of course as important in an exam as it is in coursework (have a look back at these two posts). You are going to want to spend at least 10 minutes of your hour in planning this essay, and you may want as much as 15 minutes. Remember to include your essay plan in your answer book, so that the examiner can see what you intended to say, even if you didn't get round to saying it all.

Let's say 10 minutes for an essay plan. That leaves 50 minutes for writing your essay. How much can you write in 50 minutes? That's up to you, and your own particular writing style and speed. But if you can work out some decent estimates on this before you get into the exam, you will effectively have set yourself a rough word limit for the essay. And then you can simply go back to the advice in that earlier post about paragraph structure. Work out how many words (roughly) you are going to be able to write, break that up into paragraphs, and you'll have the beginnings of a plan.

The best way of working out your writing speed is simply to set yourself some timed essays. If you don't trust your own powers of self-discipline, then get together with a friend or two to do this. Afterwards, work out how much you have been able to write by estimating the word count: count the number of lines you have written and try to work out a rough estimate of words per line, then multiply the two.

One other crucial thing to remember. Writing is a physical skill. The words on the page are formed by muscles in your hands, and those muscles need to get into shape. You will remember from previous exam periods (A-levels or whatever) how much faster you write when you have had the practice of a few weeks of exams. Get your writing hand into shape now, so that you are up to full speed when your first exam starts.

Practice writing timed essay plans and timed essays. Go back and look at what you've written, or get a friend to read it for you. How could you improve on the essay? What have you missed? What do you need to think more about or add to your notes? What are you still not clear on? This kind of practice will get you into good writing shape, and it will of course bed down the knowledge much more effectively than simply staring at your notes.

Good luck!

To show what I mean, I'm going to suggest that you go back to some of those earlier issues about structuring an essay. Remember that I suggested that you start by looking at your word limit and then work out a possible structure in terms of paragraphs. The same strategy can work in an exam.

In an exam, of course, you don't have a specific word limit. But you do have a time limit, so start with that. Let's imagine that you have a two-hour exam in which you are going to have to answer two questions: one hour per question.

Planning is of course as important in an exam as it is in coursework (have a look back at these two posts). You are going to want to spend at least 10 minutes of your hour in planning this essay, and you may want as much as 15 minutes. Remember to include your essay plan in your answer book, so that the examiner can see what you intended to say, even if you didn't get round to saying it all.

Let's say 10 minutes for an essay plan. That leaves 50 minutes for writing your essay. How much can you write in 50 minutes? That's up to you, and your own particular writing style and speed. But if you can work out some decent estimates on this before you get into the exam, you will effectively have set yourself a rough word limit for the essay. And then you can simply go back to the advice in that earlier post about paragraph structure. Work out how many words (roughly) you are going to be able to write, break that up into paragraphs, and you'll have the beginnings of a plan.

The best way of working out your writing speed is simply to set yourself some timed essays. If you don't trust your own powers of self-discipline, then get together with a friend or two to do this. Afterwards, work out how much you have been able to write by estimating the word count: count the number of lines you have written and try to work out a rough estimate of words per line, then multiply the two.

One other crucial thing to remember. Writing is a physical skill. The words on the page are formed by muscles in your hands, and those muscles need to get into shape. You will remember from previous exam periods (A-levels or whatever) how much faster you write when you have had the practice of a few weeks of exams. Get your writing hand into shape now, so that you are up to full speed when your first exam starts.

Practice writing timed essay plans and timed essays. Go back and look at what you've written, or get a friend to read it for you. How could you improve on the essay? What have you missed? What do you need to think more about or add to your notes? What are you still not clear on? This kind of practice will get you into good writing shape, and it will of course bed down the knowledge much more effectively than simply staring at your notes.

Good luck!

Thursday, February 18, 2010

'Discuss.' Discuss.

Image by Lizzie Wells via Flickr

Image by Lizzie Wells via FlickrI've just realised, that, although I've been wring essays for a while, I don't actually know exactly what one, very common key word actually means. It's "discuss". What critical / analytical tools are we supposed to bring to the command 'discuss'? It's not describe, not compare / contrast, not assess (evaluate). What does discuss actually ask you to do?Great question, and sensible to start off (as you do) by stating some of the things that 'discuss' is not. As we'll see, I think there is also a bit of 'assess (evaluate)' in 'discuss', but it's something more as well.

First, if we are to understand the beast, we need to understand where it is found. 'Discuss' questions will often start with a statement or quotation of some kind. Here's an example (picked pretty much at random from a Durham past paper):

'Most conflicts between men and women are reducible to unequal parental investment.' Explain and discuss.This is the classic 'discuss' question: it gives you something to get your teeth into (a controversial, striking or interesting statement), and then tells you to get your teeth into it. In this particular example you have a bit of 'explain' to do first: most people won't know what 'unequal parental investment' means, so you need to show that you understand that bit of the question before you can proceed.

Now here's an actual dictionary definition of 'discuss':

to consider or examine by argument, comment, etc.; talk over or write about, esp. to explore solutions; debateSo you are being asked to test out the statement in question, using reasoned argument and evidence for and against. You are being asked to be critical (which means not meekly accepting a viewpoint just because a bloke in a dodgy jumper has told it to you). And you are being asked to evaluate, which means working out, on the basis of empirical findings and reasoned argument, whether the theory/methodology/observation/interpretation/conclusion in question is a good one or not.

If the 'discuss' question doesn't have an actual statement or quotation for you to respond to, it may have the following format instead: 'Discuss the idea that...' or 'Discuss the statement that...'. Again, it's a simple matter to pull out the proposition in question, and test it out through the processes mentioned above.

'Discuss' can sometimes be used in a weaker sense, as in:

Discuss what the study of X has told us about Y.Here, you can simply plug in the words 'Write an intelligent, balanced, concise, critical, evaluative, well-supported and well-referenced essay which constructs a strong, clear argument explaining what the study of X has told us about Y.' (You can see why we prefer 'discuss'.) You're certainly being asked to do more than just describe, or to write down everything you know about the topic. In each of these scenarios you are being asked to use evidence to support an argument, draw appropriate conclusions, and all the other things we've talked about on this blog.

Friday, February 5, 2010

In flight from the banal

Image via Wikipedia

Image via WikipediaIn studying psychology at university level, you are encouraged to read widely and to consult different types of material. The things we suggest reading can include journalistic treatments of psychological matters, such as in an online news service or a pop science book. What your lecturers expect in a summative essay, though, is something a bit more academic. Writing in an academic style can be dull, but it doesn't have to be. What academic writing should always be is concise, intelligent, objective and well-referenced. We've already discussed a lot of these issues, but here are a couple more thoughts.

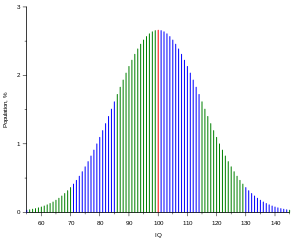

Firstly, when you read a 'journalistic' source, you will often find that the author takes some time to set the story in historical context. In academic writing, it isn't always a good idea to go too far with this, mainly because it takes up space which you could turn to better use in making your main arguments. If you're writing an essay on sex differences in intelligence, for example, you don't need to itemise all the historical developments in IQ testing. You will probably find that this information can be summarised in a line or two.

Another tip is to aim for some sort of striking introduction. You could start your essay by saying something like 'Psychologists have debated sex differences in intelligence for many years', but I might yawn. Why not choose an opening that shows that you understand the basic point and are ready to take it further? 'Although sex differences in intelligence have been of concern to psychologists for many years, there is beginning to be a consensus that any such differences are more likely to obtain in specific rather than general intelligence.' Immediately you have made a statement of interest, and can begin to build an argument.

Another difference between 'pop' sources and academic ones is fairly minor, but contributes to the impression your assignment makes. Language like 'the English psychologist Dr Charles Fernyhough, from Durham University' may go down well with a general readership, but in an academic context it is a waste of words. Chatty though we (hopefully) are on the corridor, in the world of summative assignments and journal articles (which should always be the model for your academic writing), we are not on first name terms. If you want to cite me, Fernyhough (2010) will do just fine.

Thursday, December 10, 2009

Presenting your essay

If all has gone according to plan, your essay should now be finished and ready to print out. Here are a few tips for maximising its impact.

1. Make it legible.

Put yourselves in the position of the people who will be marking your work. Your essay will make for a much more pleasant reading experience if it is double-spaced in a decent-sized font (such as Times 12 point).

2. Cut out the packaging.

There's nothing more annoying for a marker than having to extract an assignment from a plastic wallet and then slot it in again after marking. Don't use any plastic envelopes or binding—simply stapling the pages together is much easier for readers.

3. Follow the guidelines.

You will have been given guidelines (in your course handbooks and elsewhere) on referencing style, word counts, electronic submission, etc. Make sure you follow them.

4. Make it easier for your marker to give feedback.

Depending on the kind of assignment, your marker may or may not be writing comments on the essay itself. Either way, make it as easy as possible for him/her to refer to specific bits of your essay when writing feedback. Pages should be numbered, or course, but so should lines. (In Word, choose 'Document' from the Format menu. Click on the 'Layout' tab. Press the 'Line number' button and check the box, then click OK. Line numbers will appear in Page Layout View, and also when you print.)

5. Read it through.

Many errors of style, fact, argument or presentation can easily be picked up on a simple read-through. Plan the writing of your essay so as to give you a few days at the end in which you can have a break before re-reading it. Getting some distance on your work is not only good for the soul; it also allows you to gain some all-important perspective on what you have written, and to see it with fresh eyes.

I hope you've found this blog useful. I'd be very pleased to carry on in the New Year, but please let me know that you have found it helpful, and perhaps also suggest things you would like to see covered. You can email me through my departmental webpage or through my website, or else you can leave a comment right here on the blog. Have a good holiday.

1. Make it legible.

Put yourselves in the position of the people who will be marking your work. Your essay will make for a much more pleasant reading experience if it is double-spaced in a decent-sized font (such as Times 12 point).

2. Cut out the packaging.

There's nothing more annoying for a marker than having to extract an assignment from a plastic wallet and then slot it in again after marking. Don't use any plastic envelopes or binding—simply stapling the pages together is much easier for readers.

3. Follow the guidelines.

You will have been given guidelines (in your course handbooks and elsewhere) on referencing style, word counts, electronic submission, etc. Make sure you follow them.

4. Make it easier for your marker to give feedback.

Depending on the kind of assignment, your marker may or may not be writing comments on the essay itself. Either way, make it as easy as possible for him/her to refer to specific bits of your essay when writing feedback. Pages should be numbered, or course, but so should lines. (In Word, choose 'Document' from the Format menu. Click on the 'Layout' tab. Press the 'Line number' button and check the box, then click OK. Line numbers will appear in Page Layout View, and also when you print.)

5. Read it through.

Many errors of style, fact, argument or presentation can easily be picked up on a simple read-through. Plan the writing of your essay so as to give you a few days at the end in which you can have a break before re-reading it. Getting some distance on your work is not only good for the soul; it also allows you to gain some all-important perspective on what you have written, and to see it with fresh eyes.

I hope you've found this blog useful. I'd be very pleased to carry on in the New Year, but please let me know that you have found it helpful, and perhaps also suggest things you would like to see covered. You can email me through my departmental webpage or through my website, or else you can leave a comment right here on the blog. Have a good holiday.

Friday, December 4, 2009

Drawing a conclusion

You're getting towards the end of the first draft of your essay, and it's time to read back over what you've written so far. You need to be your own harshest critic here. What would you make of this essay if you were coming to it for the first time? Does the introduction set the themes up nicely? Are assertions supported? Does the argument have a logical, coherent flow? If you're having trouble judging what you've written, then ask a friend to read it for you. A fresh pair of eyes can often spot what is wrong when the author cannot.

This is the point to make changes if you are not happy with things. Are you really answering the question? Perhaps you can be more explicit about how certain findings relate to the essay title. Are you finding that bits are too digressive; that you are going off at a tangent and losing the thread of the argument? Be bold in cutting what you have written, if it makes the essay flow better. Are you evaluating the findings rigorously enough? Can you go further? Have you gone too far, and included too much of your own opinion and speculation?

Last week I noted that your conclusion should only go as far as the evidence allows it to go. Go ahead and speculate; gaze into your crystal ball at what delights future research will bring, but be clear about the limits of that kind of speculation. If you have taken other researchers to task for over-interpreting their findings, then make sure you don't fall into the same trap. If you have clearly established the limitations on the facts, then it will be clear to your reader what your basis is for any further speculation.

Don't be tempted just to repeat what you've said so far without developing it in any way. Your conclusion is the place to draw your argument together: that is bound to mean recapping on that argument, but you need to do it succinctly and in a way that builds on its meaning. For example, don't just repeat your judgement that the evidence favours Theory Y over Theory X. Put that conclusion in context, by perhaps returning to the historical background within which those theories were developed, or by highlighting some issues that are currently 'in the air', and might help to contextualise your conclusions.

A common technique in journalism is to return to the starting point for the piece. If you kicked off with a quotation, or a particular finding, then you might want to go back to it in light of what you've learned through the essay. Don't force it: that approach won't always be appropriate. But it is usually worth bearing your starting point in mind when you are considering your ending.

You're nearly there. Next week we'll talk about the all-important question of presentation.

This is the point to make changes if you are not happy with things. Are you really answering the question? Perhaps you can be more explicit about how certain findings relate to the essay title. Are you finding that bits are too digressive; that you are going off at a tangent and losing the thread of the argument? Be bold in cutting what you have written, if it makes the essay flow better. Are you evaluating the findings rigorously enough? Can you go further? Have you gone too far, and included too much of your own opinion and speculation?

Last week I noted that your conclusion should only go as far as the evidence allows it to go. Go ahead and speculate; gaze into your crystal ball at what delights future research will bring, but be clear about the limits of that kind of speculation. If you have taken other researchers to task for over-interpreting their findings, then make sure you don't fall into the same trap. If you have clearly established the limitations on the facts, then it will be clear to your reader what your basis is for any further speculation.

Don't be tempted just to repeat what you've said so far without developing it in any way. Your conclusion is the place to draw your argument together: that is bound to mean recapping on that argument, but you need to do it succinctly and in a way that builds on its meaning. For example, don't just repeat your judgement that the evidence favours Theory Y over Theory X. Put that conclusion in context, by perhaps returning to the historical background within which those theories were developed, or by highlighting some issues that are currently 'in the air', and might help to contextualise your conclusions.

A common technique in journalism is to return to the starting point for the piece. If you kicked off with a quotation, or a particular finding, then you might want to go back to it in light of what you've learned through the essay. Don't force it: that approach won't always be appropriate. But it is usually worth bearing your starting point in mind when you are considering your ending.

You're nearly there. Next week we'll talk about the all-important question of presentation.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=76321e51-61c7-4f28-99a1-51cbbfd29681)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=8f27a03f-83ad-4dee-9480-11a8c91dedc9)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=78399332-00a9-4961-ba29-e95d5ddc4318)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=3f9c6e60-1241-4480-b4dc-cf3dd5828e07)